One of the biggest influences on Pirate Ring has been Nine Man Morris. I was introduced to it under its German name Mühle when I visited the North Sea region of Germany at the age of sixteen. Alex Schmitz-Neuber challenged me to a match and I was instantly hooked by its fast gameplay and the dynamics of its compact board. How did three concentric squares pack in so much strategy?

Mühle, or Mills, or Merels, or any one of its many names, derives from a game that was played in Egypt three thousand years ago. It's likely a testament to a game needing to conform to existing constraints. In this case, think of ancient Egyptians working for a pharaoh. Let's say they were granted a short reprieve from hard labor, what could they do? In a modern context, I see them all dropping those thick ropes hauling 3-ton quarrystones and checking their mobile devices.

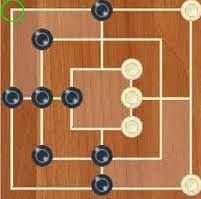

But seriously, the equivalent for an ancient people with very little leisure time might have been to draw three squares in the banks of the Nile. One opponent picks up nine dark stones off the ground and the other picks out nine lighter stones. In just a minute, they can be playing a game.

I marvel at the ease with with Mills can be played. You can imagine just about any environment on Earth supporting the basic requirements for a match-up. If you can scratch that pattern in the ground and gather some loose objects from the immediate surroundings then you can play. And remnants in Egypt show that it existed in much more durable forms, etched in clay and stone. It was one of the first casual games-- key to its success was its fastplay. Before the foreman cracked the whip for everyone to return to work, someone had already prevailed as the winner.

But just as important to the fun of Mühle is its endgame format. When one player gets down to three stones, he now may move a piece anywhere instead of just adjacent points. Suddenly the presumed loser is allowed to "level up"; it's nearly a boss-battle for the leading player. The great dynamic of suddenly setting the playing field more even (a final challenge!) makes for an often-thrilling finish.

And I sometimes wonder how the playtesting went. I imagine the game designer trying to convince friends of its merits but they complain that once he takes the lead that he just slides inevitably toward his own assured victory. They pretend to enjoy the rest of the game even when they already know they will lose, so wide is his lead. Until...

Maybe this is when another player makes a suggestion: "Why don't you change the rules and let the person with three stones now move anywhere?" she says, and eureka! suddenly his game is saved from ruin. With a simple tweak, it has endured as long as the pyramids.

Nine Man Morris is a game that I've been playing on-and-off for years, and it continues to retain significant popularity, especially in Europe. Though we now enjoy far more leisure time than ancient civilizations ever could, I nonetheless like it when strategy can be served up quickly. And I have long admired Nine Man's twist-ending, a perfect adjustment that's probably kept it relevant and compelling for three millennia.